Nadja Verena Marcin

The Great Dictator

11th september - 11th october 2019

The Great Dictator

For the solo exhibition "The Great Dictator", Nadja Verena Marcin re-enacts the The Great Dictator Speech (Los Angeles, 1940) by Charlie Chaplin, hence addresses the threatening rise of Neo-nationalism around the globe and the artist's influence potential in midst of a more politicized world. As religion has lost its place as an ethical path for many, art has ultimately risen to surrogate ethical shortfalls of late capitalism and its marks. As such, "The Great Dictator" is not only directed to a public audience but also to the art community itself.

In his prominent speech, Chaplin plays the role of the Jewish barber who has been mistaken for Hynkel — the terrifying dictator ruler of Tomainia, a clear reference to Hitler inside of the cynical anti-Nazi film. Chaplin releases a powerful speech to the people addressing their unfreedoms, calling for peace, resistance, and change. Watching his speech isolated from the film, two factors are positively unclear — who is the author and who is he speaking to? At first sight, it looks like Hitler himself is speaking, at second glance, it's a revolutionary seeking for peace, turn away from war and dictatorship, at third, we learn he has a worldwide audience.

Emphasizing the people's free will and choice in a democracy the Jewish Barber-Hynkel-Chaplin states, "You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful, to make this life a wonderful adventure. Then — in the name of democracy — let us use that power — let us all unite. (...) Let us fight for a new world — a decent world that will give men a chance to work — that will give youth a future and old age a security. By the promise of these things, brutes have risen to power. But they lie! (...) Let us fight to free the world — to do away with national barriers — to do away with greed, with hate and intolerance. (...) More than machinery, we need humanity."

Regrettably, Chaplin's words are as relevant today as they were in 1940. Seen from the eye of a female artist, Marcin's aims to shift the male leader's passionate, political and military-style speech through her performance towards a more feminine version and compare the past with the present time. The way Chaplin addresses the people is rather abstract — to study, he repeatedly viewed Riefenstahl's "Triumph of the Will" to then closely mimic Hitler's mannerism. Thus, Marcin applies the male dictator's mannerism onto her female body — bending gender and what physically represents authoritarianism — gestures mostly reserved to men.

For Chaplin, keywords for change are "progress, speed, the aeroplane, the radio, science". But, ever since his age, has science truly enlightened us and provided us with more humanity? Or, in the most unwanted scenario, is it seemingly freeing but vastly limiting at the same time? How do data profiles undermine democracy and totalitarian regimes benefit from internet spyware finding their vulnerable opponents? By quoting this backdated text and proclaiming its relevance, old-school beliefs will be held under the magnifying glass of time and handed to the observer for a deeper reflection. The priorities inside the industrial 40s, characterized by technical inventions and the first wave of consumerism, versus our time of post-industrialism and a desired about-turn of consumerism become evident. Hence, would it be possible that morality kept us in a belief of good-being and freed us outside of it? Thus, can Art now be used as a tool, an ethical license?

Marcin's piece serves to examine leadership roles — including the one of the artist and the art world but opening that question to the audience. Who are we, where do we come from and what do we expect to see? What do we expect to be freed of? — In her newest version the artist steps as a persona in the spotlight within a critical double-meaning. Whereas Chaplin is a comedian inside a film role, she is an artist inside a social role but what does acting mean ethically? In a last cry of warning, Chaplin appeals to the soldiers to change their pursuit of military servitude for the dictator. Contradictory, Marcin appeals to her own field of art experts. The word "soldiers" is replaced with "artists", asking them to stop their servitude.

As much as soldiers feels like a particular class, Marcin is addressing yet another chorus that seems isolated from the world but efficacious and financially certainly not potent. In an age driven by the media, artists have maintained enough independence, tools, and power for continuous critic and formulating questions. Hence Marcin formulates her question: "Are we, the artists, hijacked by intellectualist shelters and elite surrounding? Or are we exposed, fragile and at-risk or, more confusingly, both? Do we still seek to communicate to the people or are we caught up inside of pleasing a subculture and its hierarchal structures? Whose soldiers are we?"

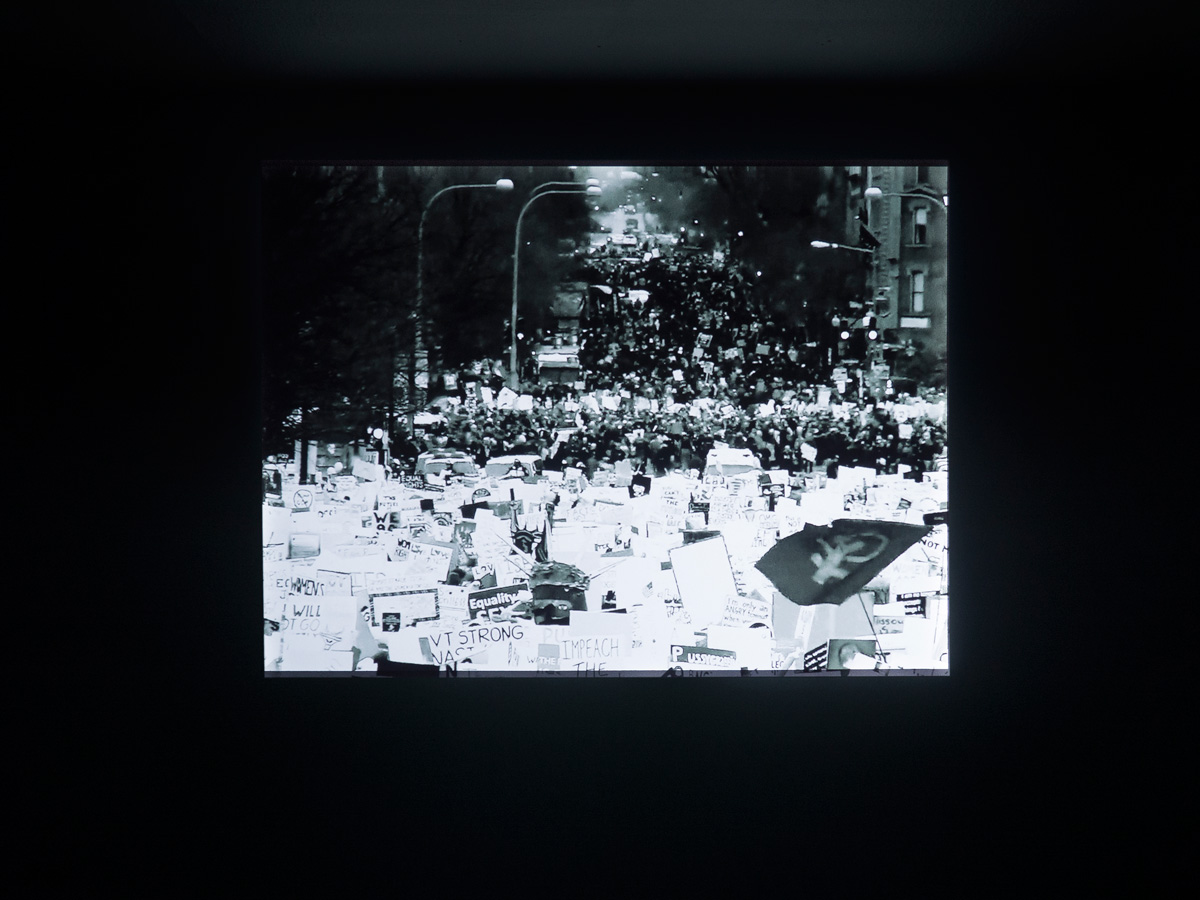

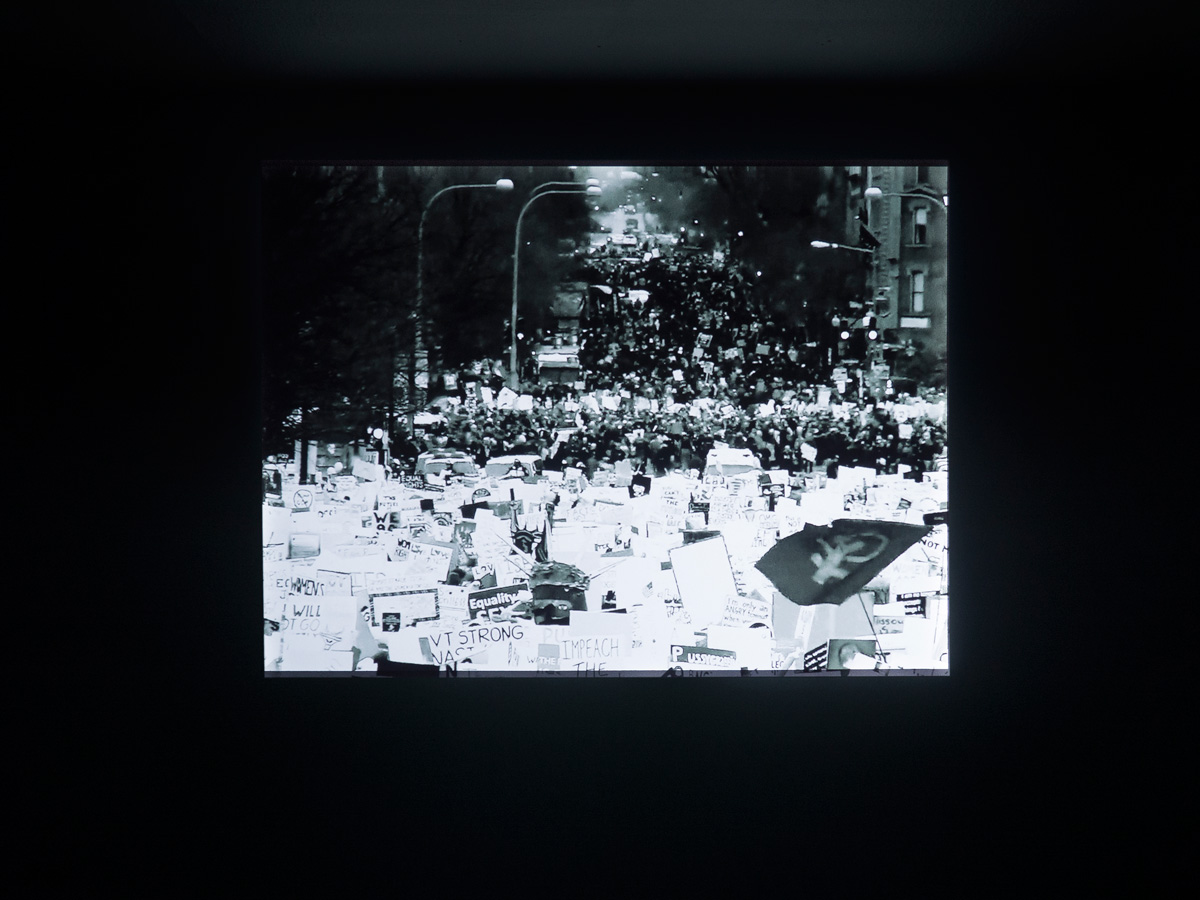

Chaplin affirms "Machinery that gives us abundance has left us in want." 79 years later, the age of the digitalization has brought a whole set of new problems, a threating potential for abuse — as seen in the 2016 US elections. On the positive side, also democratic movements have risen and formed strong communities. Suddenly, there is more performativity around media and who is given the voice. But the premise that modern communication would dissolve boundaries remains unfulfilled. Instead, we see an architecture of behavior of taste and likes, the daily yes and no making — within scales of preference, resembling structures of fascism.

In his autobiography, Chaplin quotes himself as having said: One doesn't have to be a Jew to be anti-Nazi. All one has to be is a normal decent human being. Chaplin biographer David Robinson writes in the "The Spectator" dated 21st April 1939, "There was something uncanny in the resemblance between the Little Tramp and Adolf Hitler, representing opposite poles of humanity." Similarly, there is that thin line between good and evil inside the art world, being trapped within its financial ruin dependent on those affluent with accumulating capital; a silent clown for purpose.

Chaplin and Hitler have excelled in expressing the sentiments and aspirations of millions of citizens between the upper and lower millstones. Both mirror the predicament of the little man in modern society — raising to power, one for the good, one for the evil. But this it is where the disguise begins. Inside the art world, we are not addressing the little man. Via the video-performance of performing-the-comedian-that-performs-the-dictator Marcin draws a metaphor to the functioning of Kulturindustrie, she states "Not only do I seek to generate response but also would I like to ask that pertinent question of the attention economy in a more significant way — who are you, where are you at and what do you want to believe?"

Alle Fotos (c) Betty Böhm, courtesy Nadja Verena Marcin, 2019

nadjamarcin.com

The Great Dictator

11th september - 11th october 2019

The Great Dictator

For the solo exhibition "The Great Dictator", Nadja Verena Marcin re-enacts the The Great Dictator Speech (Los Angeles, 1940) by Charlie Chaplin, hence addresses the threatening rise of Neo-nationalism around the globe and the artist's influence potential in midst of a more politicized world. As religion has lost its place as an ethical path for many, art has ultimately risen to surrogate ethical shortfalls of late capitalism and its marks. As such, "The Great Dictator" is not only directed to a public audience but also to the art community itself.

In his prominent speech, Chaplin plays the role of the Jewish barber who has been mistaken for Hynkel — the terrifying dictator ruler of Tomainia, a clear reference to Hitler inside of the cynical anti-Nazi film. Chaplin releases a powerful speech to the people addressing their unfreedoms, calling for peace, resistance, and change. Watching his speech isolated from the film, two factors are positively unclear — who is the author and who is he speaking to? At first sight, it looks like Hitler himself is speaking, at second glance, it's a revolutionary seeking for peace, turn away from war and dictatorship, at third, we learn he has a worldwide audience.

Emphasizing the people's free will and choice in a democracy the Jewish Barber-Hynkel-Chaplin states, "You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful, to make this life a wonderful adventure. Then — in the name of democracy — let us use that power — let us all unite. (...) Let us fight for a new world — a decent world that will give men a chance to work — that will give youth a future and old age a security. By the promise of these things, brutes have risen to power. But they lie! (...) Let us fight to free the world — to do away with national barriers — to do away with greed, with hate and intolerance. (...) More than machinery, we need humanity."

Regrettably, Chaplin's words are as relevant today as they were in 1940. Seen from the eye of a female artist, Marcin's aims to shift the male leader's passionate, political and military-style speech through her performance towards a more feminine version and compare the past with the present time. The way Chaplin addresses the people is rather abstract — to study, he repeatedly viewed Riefenstahl's "Triumph of the Will" to then closely mimic Hitler's mannerism. Thus, Marcin applies the male dictator's mannerism onto her female body — bending gender and what physically represents authoritarianism — gestures mostly reserved to men.

For Chaplin, keywords for change are "progress, speed, the aeroplane, the radio, science". But, ever since his age, has science truly enlightened us and provided us with more humanity? Or, in the most unwanted scenario, is it seemingly freeing but vastly limiting at the same time? How do data profiles undermine democracy and totalitarian regimes benefit from internet spyware finding their vulnerable opponents? By quoting this backdated text and proclaiming its relevance, old-school beliefs will be held under the magnifying glass of time and handed to the observer for a deeper reflection. The priorities inside the industrial 40s, characterized by technical inventions and the first wave of consumerism, versus our time of post-industrialism and a desired about-turn of consumerism become evident. Hence, would it be possible that morality kept us in a belief of good-being and freed us outside of it? Thus, can Art now be used as a tool, an ethical license?

Marcin's piece serves to examine leadership roles — including the one of the artist and the art world but opening that question to the audience. Who are we, where do we come from and what do we expect to see? What do we expect to be freed of? — In her newest version the artist steps as a persona in the spotlight within a critical double-meaning. Whereas Chaplin is a comedian inside a film role, she is an artist inside a social role but what does acting mean ethically? In a last cry of warning, Chaplin appeals to the soldiers to change their pursuit of military servitude for the dictator. Contradictory, Marcin appeals to her own field of art experts. The word "soldiers" is replaced with "artists", asking them to stop their servitude.

As much as soldiers feels like a particular class, Marcin is addressing yet another chorus that seems isolated from the world but efficacious and financially certainly not potent. In an age driven by the media, artists have maintained enough independence, tools, and power for continuous critic and formulating questions. Hence Marcin formulates her question: "Are we, the artists, hijacked by intellectualist shelters and elite surrounding? Or are we exposed, fragile and at-risk or, more confusingly, both? Do we still seek to communicate to the people or are we caught up inside of pleasing a subculture and its hierarchal structures? Whose soldiers are we?"

Chaplin affirms "Machinery that gives us abundance has left us in want." 79 years later, the age of the digitalization has brought a whole set of new problems, a threating potential for abuse — as seen in the 2016 US elections. On the positive side, also democratic movements have risen and formed strong communities. Suddenly, there is more performativity around media and who is given the voice. But the premise that modern communication would dissolve boundaries remains unfulfilled. Instead, we see an architecture of behavior of taste and likes, the daily yes and no making — within scales of preference, resembling structures of fascism.

In his autobiography, Chaplin quotes himself as having said: One doesn't have to be a Jew to be anti-Nazi. All one has to be is a normal decent human being. Chaplin biographer David Robinson writes in the "The Spectator" dated 21st April 1939, "There was something uncanny in the resemblance between the Little Tramp and Adolf Hitler, representing opposite poles of humanity." Similarly, there is that thin line between good and evil inside the art world, being trapped within its financial ruin dependent on those affluent with accumulating capital; a silent clown for purpose.

Chaplin and Hitler have excelled in expressing the sentiments and aspirations of millions of citizens between the upper and lower millstones. Both mirror the predicament of the little man in modern society — raising to power, one for the good, one for the evil. But this it is where the disguise begins. Inside the art world, we are not addressing the little man. Via the video-performance of performing-the-comedian-that-performs-the-dictator Marcin draws a metaphor to the functioning of Kulturindustrie, she states "Not only do I seek to generate response but also would I like to ask that pertinent question of the attention economy in a more significant way — who are you, where are you at and what do you want to believe?"

Alle Fotos (c) Betty Böhm, courtesy Nadja Verena Marcin, 2019

nadjamarcin.com

↵

| zqm/info(at)zqmberlin.org | impressum/(c)zwanzigquadratmeter 2025 |